Brian Steven Smith has been sentenced to 226 years in prison for the deaths of two Native Alaskan women, Kathleen Jo Henry and Veronica Abouchuk.

Smith was found guilty in February on 14 criminal counts, including first and second-degree murder, tampering with evidence and sexual assault in the deaths of both women. He declined to speak at Friday’s hearing and did not speak at all throughout the trial.

The 226-year sentence matches the length recommended by prosecutors from the Anchorage District Attorney’s office, Brittany Dunlop and Heather Nobrega.

Smith’s defense attorney, Timothy Ayer, recommended a 132-year sentence, arguing that his client would be in prison for the rest of his life either way.

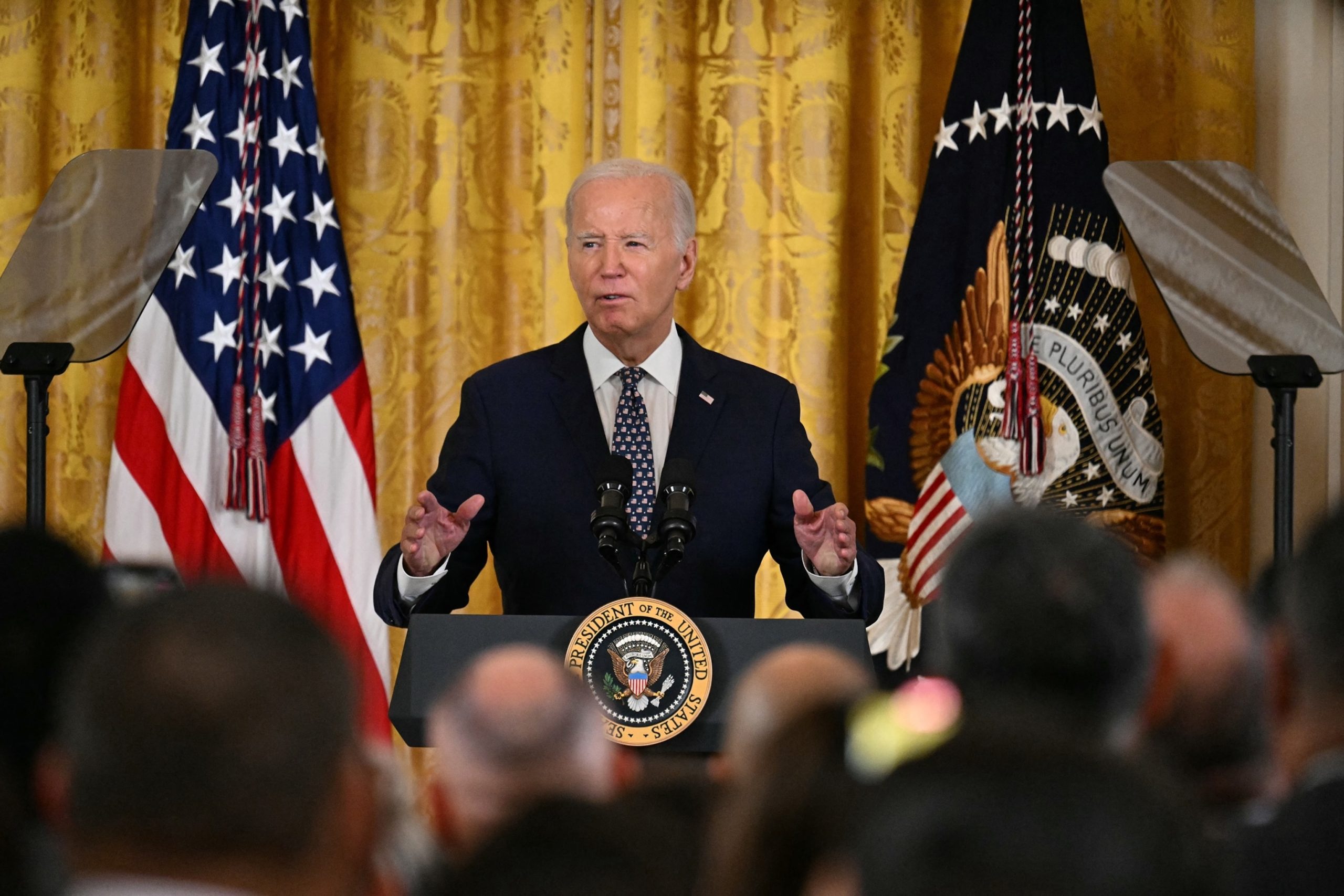

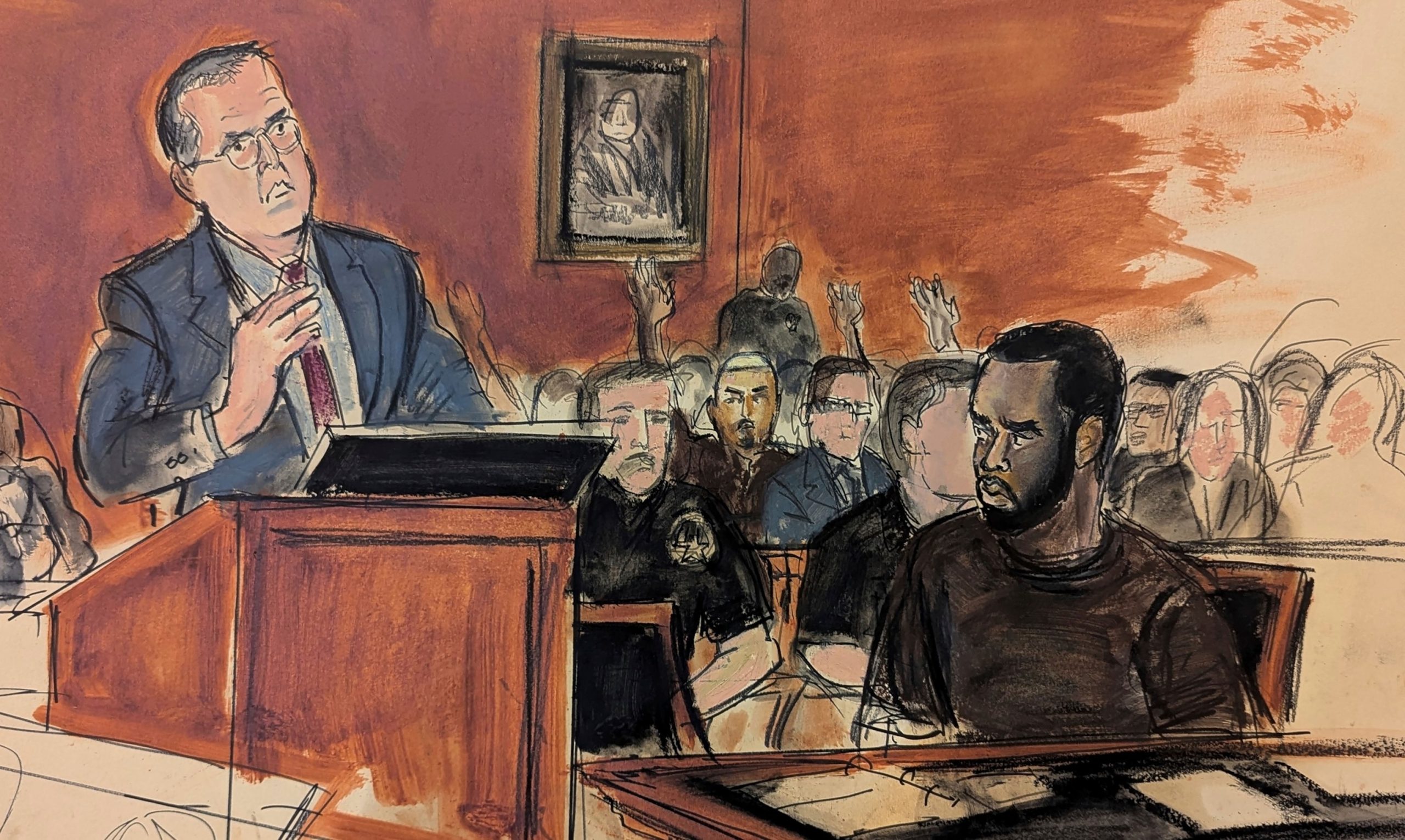

Brian Steven Smith sits in a courtroom while waiting for his arraignment to start in Anchorage, Alaska, Oct. 16, 2019.

Mark Thiessen/AP

Before Friday’s sentencing hearing, the prosecution released photographs found on Smith’s phone and a forensic sketch of an unidentified Native Alaskan or Asian woman who is believed to be a third possible victim in these crimes.

Smith discussed the images in an interview with Anchorage police that played in court during his trial.

The prosecution said the photos establish a pattern of violence.

“As long as I’ve been doing this work, I still believe that most people are good and there are very, very few truly evil humans in the world. Mr. Smith is one of them,” Dunlop said at Friday’s sentencing. “He is a person that should never be permitted to walk among us. He should spend the rest of his life in jail and your sentence should make a statement that the women’s lives that he stole so brutally mattered.”

During the trial, prosecutors presented graphic video and photo evidence, captured by Smith himself, of Smith narrating his actions during Henry’s murder.

Kristy Grimaldi, Abouchuk’s daughter, spoke at the sentencing hearing, following her appearance at the trial earlier this year.

“It’s a relief knowing that the defendant will rot. I hope he is swarmed with guilt someday knowing he stalled so many people’s joy,” Grimaldi said. “To me, he will always be an unintelligent sick human being who couldn’t comprehend the meaning of life.”

Judge Kevin Saxby, who has been presiding over Smith’s case since the trial began in February, said before pronouncing the sentence that the killings of Abouchuk and Henry have a larger effect on society, especially for women.

Rena Sapp, outside a courtroom, Oct. 21, 2019, in Anchorage, Alaska, shows a photo of her sister, Veronica Abouchuk, taken during a day out shopping in 2013.

Mark Thiessen/AP

“Those killings actually affect all of society, and especially women in our society. It’s the stuff of nightmares,” Saxby said, “They strip women of any feelings of safety in their own neighborhoods. That damage continues long after the crimes are solved.”

At the beginning of Friday’s sentencing, Saxby said that though it is standard practice to use initials when referring to victims, he would like to use the victims’ full names.

“They were treated as something other than human, and they were dehumanized,” Saxby said. “It seems to me that the more respectful thing to do is to refer to them by name… and that will help actually, to some tiny extent restore their personhood.”

Grimaldi echoed this sentiment in her remarks about her mother, saying, “Forget the defendant’s name and remember: Veronica Rosaline Abouchuk and Kathleen Jo Henry.”

Brian Steven Smith, a 48-year-old man from South Africa, has been sentenced to 226 years in prison for the brutal murders of two Native Alaskan women. The sentencing comes after a lengthy trial that captivated the nation and shed light on the issue of violence against Indigenous women in the United States.

The case began in September 2019 when the remains of 30-year-old Veronica Abouchuk and 52-year-old Kathleen Henry were discovered in a remote area outside of Anchorage, Alaska. Both women had been reported missing earlier that year, and their deaths sent shockwaves through the tight-knit Native Alaskan community.

Smith, who had been living in Alaska at the time of the murders, was quickly identified as a suspect and arrested by authorities. During the trial, prosecutors presented evidence that linked Smith to the killings, including DNA evidence found at the crime scenes and surveillance footage showing him with the victims before their deaths.

Throughout the trial, Smith maintained his innocence, claiming that he had been framed by law enforcement. However, the jury ultimately found him guilty on multiple counts of murder, sexual assault, and evidence tampering.

The sentencing of Smith to 226 years in prison has been hailed as a victory for the families of the victims and advocates for Indigenous rights. It serves as a reminder of the ongoing issue of violence against Native women in the United States, who are disproportionately affected by homicide and sexual assault.

According to a report by the Urban Indian Health Institute, more than 5,700 Indigenous women and girls were reported missing in 2016, with many cases going unsolved or uninvestigated. The high rates of violence against Native women have been attributed to a lack of resources, systemic racism, and jurisdictional issues that make it difficult for law enforcement to effectively investigate crimes on tribal lands.

In response to these challenges, lawmakers have introduced legislation such as Savanna’s Act and the Not Invisible Act, which aim to improve coordination between federal, state, and tribal authorities in cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women. These efforts are crucial in addressing the root causes of violence against Native women and ensuring that perpetrators are held accountable for their crimes.

As the sentencing of Brian Steven Smith demonstrates, justice can be served for victims of violence, even in cases where the perpetrators try to evade responsibility. It is a step towards healing for the families of Veronica Abouchuk and Kathleen Henry, and a reminder that no one is above the law when it comes to committing acts of violence against Indigenous women.